Source: Robert Scribbler

It’s the highest mountain range in the world. Featuring peaks that scrape the sky, dwindling glaciers, and lush forests, these gentle giants are essential to the prosperity and stability of one of Asia’s greatest lands. For rainwater and glacial melt flowing out of the Himalayas feeds the rivers that are the very life-blood of India and her 1.25 billion people.

A major wildfire burns through the forests of Ahirikot in Srinagar, India on Monday, May 2, 2016. Massive wildfires that killed at least seven people over recent days burned through pine forests in the Himalaya mountains of northern India on Monday. (Image source: Press Trust of India)

But in 2016, amidst what is likely to be the most intense period of extreme heat to ever impact India, the Himalayas are burning.

Extreme Heat, Drought Kills Hundreds, Displaces Farmers, Puts Towns on Life Support

Throughout April and into early May temperatures have soared to well above 104 degrees Fahrenheit (40 C) and to sometimes higher than 122 F (50 C) all across the broad plains at the feet of the Himalayas. There, water stress now affects more than 330 million people. There, water trains are now necessary to keep whole towns from suffering dehydration. Farmers who have seen fields transformed into a baked white hard-pan are migrating to the cities in search of food, water and work. And armed guards now patrol the local water sources in regions hardest hit by the drought — preventing private farmers from stealing public water supplies for their crops.

The temperatures are so high that more than 300 people have now perished as a result of heat injuries. And Indian officials have now banned cooking during the day in an effort to reduce loss of life. But today the forests themselves are cooking as the air is filled with the smoke of more than 21,000 fires burning upon the flanks of India’s great mountain ranges.

21,000 Himalayan Wildfires

The fires began as early as February after a dry Winter and two years of depleted monsoonal rains. They continued to build through March and April. State firefighters were called up to combat the blazes, but to no avail. The fires kept growing and expanding. By last week the fires had begun to rage out of control — threatening 84 villages and enveloping more and more of the precious natural forest reserves that India has worked so hard to husband. By Monday, seven people had been killed by the fires and two endangered tiger preserves had been partially consumed.

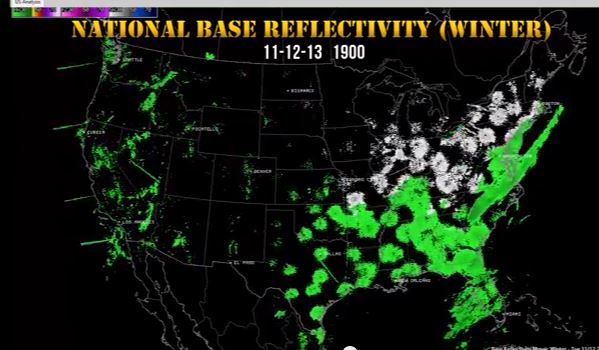

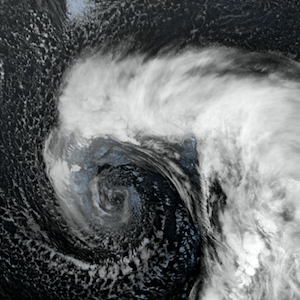

Massive plume of smoke from Himalayan wildfires becomes visible in the LANCE MODIS satellite shot on May 1, 2016. For reference, bottom edge of frame is about 600 miles.

Now conditions are so extreme that an army of 9,000 firefighters, including helicopter fire suppression craft, have been mobilized by the government of India in a desperate effort to beat back the flames. Blazes that are belching out thick clouds of smoke that now choke the airs over 1,000 miles of the Indian subcontinent, the Bay of Bengal, Bangladesh, Thailand and Cambodia. A thickening slate-gray pall that is clearly visible in the satellite picture above.

In total, more than 21 districts in two Indian states are now affected by the most intense fire situation to strike India since 2012 and what could well become the worst burning season India has ever experienced. Already, number of fires started in the first four months of 2016 exceed the total number of fires during all of 2015. And India’s hottest months — May and June — are still ahead. So despite a massive firefighting effort, weather conditions will only continue to worsen during the weeks ahead. Meanwhile, the monsoonal rains, if they do muster sufficient strength to alleviate the drought, will not arrive in the mountains until late June or early July.

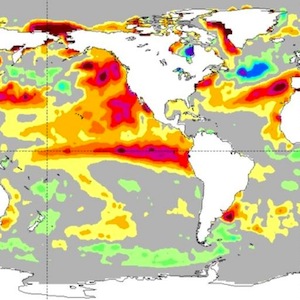

A Context of Climate Change

Weak monsoonal rains over the past two years have contributed to 2016’s severe drought and related wildfires. And a strong El Nino has likely abetted this monsoonal weakening. However, increasing global temperatures set up an overarching trend of heating and drying throughout India. One that is, all-too-likely, the larger driver of this year’s drought and burning. For these days, atmospheric temperatures are high enough to weaken the Southeast Asian Monsoon even without the influence of El Nino. In addition, rising temperatures over India have their own localized drying effect. In the Himalayas, a warming of about 0.6 degrees C per decade since 1977 has generated a decline in glaciers. This decline causes mountain streams and rivers to dwindle — increasing both drought and fire risk. The added heat also increases the rate of evaporation — parching the soil.

As a result, the current drought, heatwaves, and wildfires in India occur in a context of human-caused climate change. Hitting an intensity we would not have seen in the world of the 19th and 20th Centuries. Thus, fossil fuel burning has, almost certainly, set the stage for the unprecedented conditions that India is now experiencing today. Conditions that will continue to worsen as more hothouse gas emissions hit the world’s airs. The current crisis in India should, therefore, not be viewed as temporary, but as part of an ongoing trend.

Links:

Wildfires Sweep Through Mountains in North India

With Climate Change, Himalayas Future is Warmer, Not Brighter

Wildfire Engulfs 3,000 Hectarces in Himachal

Thousands Sent to Fight Wildfires in Himalayan Foothills of India

More Than 300 Million People Now Suffer From the Worst Indian Drought in at Least 4 Decades

Armed Guards Now Patrol Dams in India

Source: Robert Scribbler