Source: The Boston Globe, written by David Abel

The Big Unchill

The Arctic ice is melting faster than ever recorded, the warmth tied to the emissions of modern life. But it is the ancient ways at the top of the world that are most at risk.

BARROW, Alaska — A mile off the coast of the continent’s northernmost city, Josh Jones gunned his four-wheeler over ridges of buckling ice and through pools of turquoise water, where normally there would be a vast sheen of ice and snow.

Escorted by an Eskimo guard toting a shotgun to protect them from roving polar bears, Jones and a fellow climate researcher were racing to retrieve scientific instruments that gauge the thickness of the ice, which they worried could be lost to the uncommonly rapid melt of the Arctic Ocean.

They were also in a race with much bigger stakes.

In previous years when making the trip out here to set up their observatory, temperatures had been so raw that Jones’s eyelids froze. On this day early last month, it was a balmy — for Barrow — 41 degrees. When they arrived at the observatory, which was surrounded by sprawling melt ponds, they stripped off their parkas and rolled up their sleeves.

Their wind turbine and other equipment had collapsed in the melting ice. They’d almost lost their all-terrain vehicle, too, when it lurched into a sinkhole and stalled in a knee-deep pool of slush.

“Not a good sign,” Jones deadpanned.

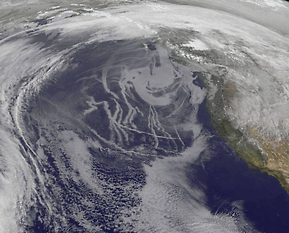

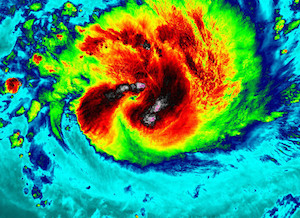

Here, as close to the top of the world as you can get in America, the signs are serious indeed: The Arctic Ocean is melting faster than at any time on record. This February, the sea ice that stretches from North America to Russia reached its lowest-known winter extent and began melting 15 days earlier than usual. That continued a three-decade trend that has seen the ocean’s ice lose about 65 percent of its mass and about half of its reach during the summer. In 20 or 30 more years, the Arctic Ocean could be nearly devoid of ice in the summer, climate scientists believe.

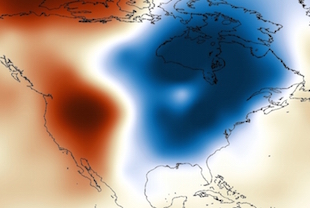

SOURCE: Stanford Report," September 30, 2014; Skeptical Science, "A Rough Guide to the Jet Stream"

James Abundis / Globe Staff

But the changes that are incipient here in New England are already acute in Barrow, where the average temperature has risen 3.6 degrees since 1921 — more than twice the rise of average global temperatures.

“Barrow is among the fastest-warming land areas in the world,” said Rick Thoman, a climate scientist at the National Weather Service in Fairbanks.

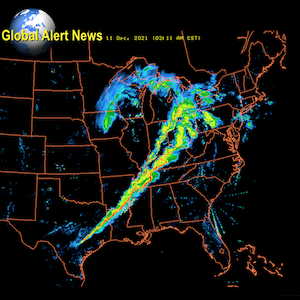

SOURCE: National Weather Service Alaska Region

James Abundis / Globe Staff

And the effects on the way of life here — long preserved against change by remoteness and the desperate cold — have been profound. Life as they knew it for the 4,300 who call this treeless tract of tundra 300 miles north of the Arctic Circle home is beginning to feel irretrievable.

No one knows that better than the Iñupiat Eskimos, whose ancestors first settled here 1,500 years ago and who still constitute more than half of the local population on this stark, triangular spit of land where beached whale bones litter the black gravel shore.

The Iñupiat have long survived brutal winters when the sun doesn’t rise over the snowbound city of wooden homes for two months and summers when the ground turns to spongy black mud and the sun never sets. No roads lead to Barrow from elsewhere in Alaska, so they have learned to provide for themselves.

But now they are watching as the sheets of ice that have long encased the nearby Chukchi and Beaufort seas — where they hunt seals, walruses, and whales — are melting significantly earlier and returning later than ever before. The shores off Barrow typically remained covered in ice well into July and would refreeze in October.

Melt ponds now often start forming in May, and the massive sheets now typically break up in June. Since 2002, the ocean has not frozen over in October, according to the National Weather Service.

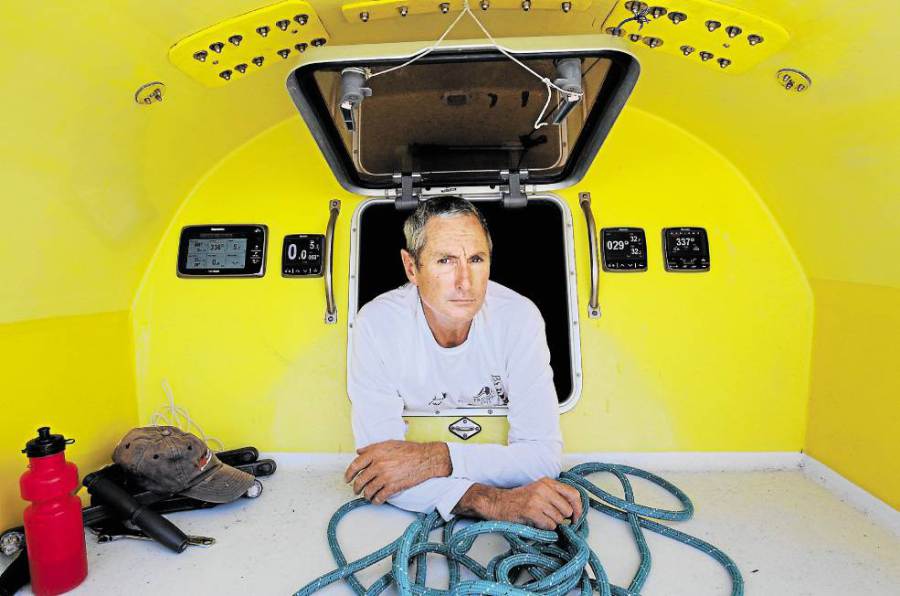

The changing climate is having a mounting effect on men such as Harry Brower Jr., who grew up hunting bowhead whales, ringed seals, king eiders, and other prey to feed his family. The 58-year-old captain of an umiak, a traditional seal-skin whaling boat, has found he can no longer rely on lessons passed through the generations.

Hunting is such a part of the city’s history that the Iñupiat name for Barrow is Ukpeagvik, which means “the place where we hunt Snowy Owls.” But all the time-tested patterns along the North Slope of Alaska — the currents, weather patterns, ice thickness, and the timing of whale migrations, among other things — have become less predictable.

“Everything’s changing,” Brower said. “It requires us to be more observant.”

Whales now often pass through local waters earlier in the year than they used to, and Brower and his crew have had to hunt in significantly less sunlight. That has made it more dangerous to haul their umiaks to the distant edges of the ice, where they build shelters and spend weeks stalking the massive mammals. Several years ago, he said, one crew got stranded when an ice sheet broke off unexpectedly. About 40 men had to be rescued by helicopter, and they lost all of their equipment.

“If we don’t have access to the ice, we can’t hunt,” Brower said.

Harry Brower Jr., captain of a whaling boat, has found that because of climate change, he can no longer rely on hunting lessons passed through the generations. David L. Ryan/Globe Staff

The warming has also forced local officials to do what they can to defend Barrow, where the natural forces are visible in the beached, broken fishing boats lining the shore and muted, weather-beaten homes mired in brown pools of ice melt.

Edward Itta, who served for much of the past decade as mayor of the region that includes Barrow, said the increasingly unsettled earth has destabilized roads and triggered expensive failures in water and sewer systems.

He and other residents are also concerned that the permafrost, the frozen ground underlying Barrow, is thawing at greater depths and releasing a surging amount of methane — a greenhouse gas 25 times more potent than carbon dioxide.

The melting earth has flooded and ruined residents’ ice cellars, which they carve out of the frozen ground, forcing them to scramble to prevent their prized stocks of whale and seal meat from spoiling.

“A lot of things we were taught don’t really apply anymore,” Itta said.

Last year, the 69-year-old was shocked when his 22-foot aluminum motorboat couldn’t make it through coastal waters and up rivers for his annual summer hunting trip. The winds — unlike anything he had experienced before — were too strong, and the rivers, whose waters are being absorbed by the thawing ground, were too shallow.

“The change is real, and we’re feeling it accelerating,” he said.

Officials have sought to protect Barrow, Alaska, which is fewer than 15 feet above sea level, by moving municipal buildings and lining the coast with berms and sandbags. David L. Ryan/Globe Staff

The frozen Arctic Ocean has long served as something of a heat vent for the rest of the planet, its millions of square miles of snow-covered ice reflecting sunlight back into space. But the receding ice has meant more energy is being absorbed by the open ocean, a self-reinforcing cycle that has increased sea and land temperatures, according to the National Snow and Ice Data Center in Boulder, Colo.

The warming has resulted in the surrounding tundra greening with a proliferation of lichens and shrubs. Walruses and polar bears are losing the icy habitat where they have always hunted, while migration patterns of marine life and some seabirds are also shifting.

Several miles offshore from Barrow on Cooper Island, the decimation of a colony of black guillemots provides a stark example of the destruction, said George Divoky, a zoologist who has spent the past 41 summers studying the seabird colony.

With coastal waters 6 degrees warmer in recent summers than when he started his study, the number of guillemots that nest on the island has plummeted by half as they struggle to find their primary source of food, Arctic cod, which have moved farther offshore in search of cooler, ice-filled waters, he said. Now, only about half as many chicks survive as once did.

“We’re watching a disaster unfolding,” Divoky said while waiting last month for a helicopter to ferry him the few miles from Barrow to the island because it was no longer safe to travel by snowmobile over the melting ice.

When he finally made it to the island, he found the guillemots were already laying their eggs — earlier than in any previous year of his study.

Josh Jones worked to get his ATV out of water on the ice near Barrow, Alaska. David L. Ryan/Globe Staff

Flooding is also a growing threat in Barrow. With less of a buffer from the ice sheets, which have long kept currents in check and buffered the coast, more powerful storms and waves have become common. As a result, many of the local beaches have been eroding twice as fast as they did in the 1950s, said Anne Jensen, an archeologist at the Barrow Arctic Research Center.

James Abundis / Globe Staff

“We’re seeing large amounts of land falling into the sea,” Jensen said while showing pictures in her cramped office of the eroding shore.

She worries that the city’s history, long preserved by the cold, dry conditions, is increasingly at risk. The warmer, wetter weather has accelerated the decomposition of bones, tools, and other relics of those who first settled in the area.

“We’re hitting a tipping point,” Jensen said. “Heritage that has been preserved for hundreds, if not thousands, of years is going to be lost in a matter of a few decades.”

Since Josh Jones’s team began tracking Barrow’s sea ice in 1999, the researchers have seen it thin by an average of 10 percent.

“That’s quite a big difference in such a short time,” said Andy Mahoney, a professor of geophysics who oversees the team’s research at the University of Alaska in Fairbanks.

The main source of melting used to be the sun beating on the ice, he said. Now, more of the melt comes from below, as the open ocean absorbs more sunlight and changing currents pulse the saltier, warmer waters of the North Atlantic through the Arctic.

As the researchers bored into the ice to take their final measurements, Mike Thomas, their guard, scanned the horizon for polar bears. Snacking on seal meat, he spoke of how years-old ice used to form towering ridges over the frozen ocean and how it was common for winter temperatures to plummet to 40 below or lower.

Jones told stories about previous trips on the ice when he had to use pliers to break the ice on a colleague’s mustache to help him breathe and how he once fell off his snowmobile into a moat of frigid water between the beach and the ice.

“It’s not something you want to repeat,” he said.

Late in the afternoon, with a sun that wouldn’t set for months still high in the sky, a cold front moved in, pelting the men with sleet. The researchers packed their equipment onto sleds and climbed back on their four-wheelers, sloshing through more melt ponds and slush on their way back to the solid ground of the beach.

Two weeks later, the ice pack melted and what remained began moving offshore — the earliest it had broken up in the past decade, according to the National Weather Service.

By the end of the month — Barrow’s warmest June on record — the remaining floes had drifted more than 10 miles out to sea, vanishing from view of the shore.

Source: The Boston Globe, written by David Abel

3 Responses

This is also a real eye opener. > Professor Peter Wadhams

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=8xdOTyGQOso#t=403

Peter Wadhams ScD (born 14 May 1948), is professor of Ocean Physics, and Head of the Polar Ocean Physics Group in the Department of Applied Mathematics and Theoretical Physics, University of Cambridge. He is best known for his work on sea ice.

Very sobering article. I wonder about the 'pole flip' scenario, and how might that factor into any of this. They claim on average this 'flip' has occurred about every 200,000 yrs. (if memory serves me correctly from carbon dating volcanic rock and soil samples) and we are well overdue for one. I am sure man's tinkering with the natural order of things is also a major factor- besides being a really BAD IDEA! I learned of this from a Nova program called 'Magnetic Storm' and highly recommend watching it to others. Whatever is causing it, we sure look like we are on a short time frame for big changes. This kind of rapid shift does not allow for species to adjust in their evolution to survive the elements. My heart is very sad to hear this news and I pray for Divine Intervention for us all.

What an excellent article and shows how fast climate events are unfolding. Maybe Guy McPherson got it right that we have no later than 2030 before it's lights out for the planet.